Learning Planet Festival Recap: a2ru’s Artistic Research for Future Challenges

Apr 18, 2023

On January 27, 2023, a2ru hosted a discussion on the topic of leveraging “Artistic Research for Future Challenges” as part of the global Learning Planet Festival. A2ru is a member of the LearningPlanet Alliance, created in 2020 by UNESCO and the Learning Planet Institute, intended to galvanize networks to take care of human and planetary health by transforming education. a2ru is one of the few arts organizations in this global network but pretty much everyone in Learning Planet is connected to and values the arts as a game-changer in this realm. We were happy to have a session as part of the festival this year.

(For more about what LearningPlanet is doing, read their “Clarion call to change course and transform education.” a2ru also participates in “Exploring Critical Transitions in Higher Education for Planetary Health” and we will have a brief write up of that session as well, coming soon!)

The roundtable we convened around artistic research included: Aaron Knochel, Professor, Penn State University; R. Benjamin Knapp, Director, Institute for Creativity, Arts, and Technology (ICAT), Virginia Tech; Raphaële Bidault-Waddington, Artist-Researcher and Futurist, LIID Future Lab; and Theo Edmonds, Theo Edmonds, Culture Futurist ™ and leads University of Colorado Denver’s Imaginator Academy,, all of whom have a lot going on in terms of testing the waters in artistic research and transdisciplinary, arts-integrated work.

We had a very lively and messy conversation on this broad topic. To better understand how artistic research can help with systemic, societal problems, one thing we wanted to do was to ground the roundtable’s discussion by addressing conceptions of creativity. We also wanted to deepen our shared understanding of disciplinarity to set the stage for expanding our notions of research and innovation. The researchers and leaders covered a lot of ground and are each in their own way constructing a solid foundation for future work in this area. This write-up is a summary of the conversation; you can view the full video and download the slide deck below.

Revisiting Common Notions of “Creativity” (Spoiler: Not all artists are creatives!)

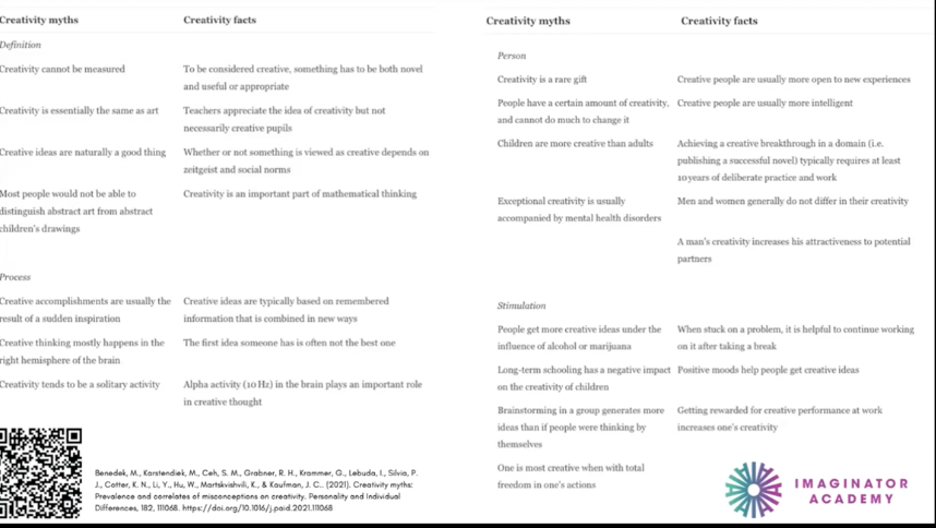

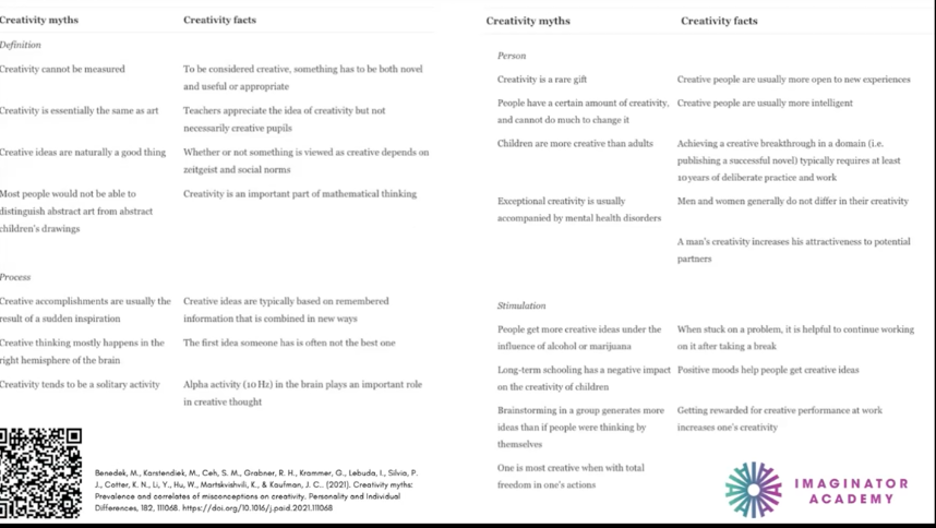

Building on a shared article prior to the session [“Creativity Myths: Prevalence and correlates of misconceptions on creativity”], Theo Edmonds notes that “The revenue production models of today’s media often do not allow for a full, nuanced discussion of the science behind creativity demands. This results in a confusion between myths and facts about what the science behind creativity actually shows.”

“When thinking about creativity, I encourage everyone to pause before rushing fast to conclusions. Take a fresh assessment and really look at where creativity sciences are today. There is so much more to creativity than just divergent thinking which is where most people get stuck. And, aided by technology and neuroscience advancements, creativity sciences are poised to make an exponential jump in the very near future.”

Edmonds leads the global creativity sciences workgroup within Barcelona’s Brain Capital Alliance; and his work with the Imaginator Academy looks at many research questions as we move from an industrial economy to a brain economy. Among those question are:

- What is the process of quantifying creativity as a latent capacity within an economy or within a company?

- What are the culturally-responsive protocols to unlock that creative capacity once identified?

- Where are there big, disruptive opportunities on the horizon for creative capacity to breakthrough as enterprise-wide value?

That value of creativity for companies could be social for a company that is doing corporate social responsibility work or social impact; or it could be economic in terms of commercializing a new product and service.

Together with a growing group of collaborators, Theo and his colleagues are also focused on an artist innovation residency model as the catalyst to find the answer to these questions; and the work is guided by quantitative cultural analytics and data.

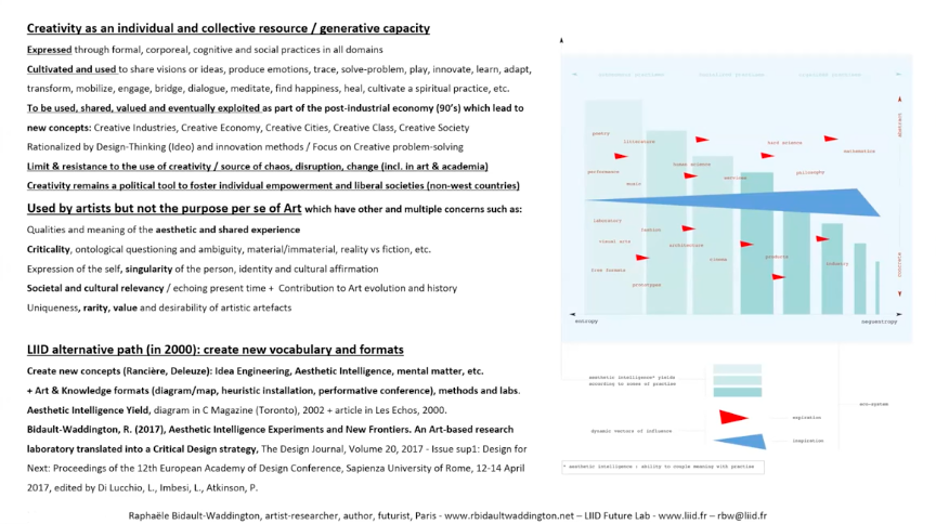

Introducing a new vocabulary

Since the late 90’s, Raphaële Bidault-Waddington has organized her art practices as laboratories, each having a specific formal language (photo-based work, conceptual diagrams, drawing, textile creation, etc.) and exploring certain questions. Among them, LIID (Laboratoire d’Ungénierie d’IDées / IDea Engineering Laboratory) is the most immaterial one, and today the most active. It focuses on art-based knowledge, on knowledge aesthetics (e.g. diagrams), and on the aesthetics of organizations (also intangible shapes). The aim of LIID is to innovate in practice and in theory, at the crossroad of artistic research and knowledge production (including a reflection on conceptual art, economic and science histories), and to experiment collaborations with organizations to bridge art with other domains (business, academia, urban studies, innovation, and now future studies).

“Creativity is a shared resource in society…it’s an individual and collective resource.”–Bidault-Waddington

As an artist, she saw creativity as something different from Art: “creativity is a shared resource in society…it’s both an individual and collective resource. It is a generative capacity that is used in many contexts and is not specific to art. It belongs to society.”

She recalled that at the turn of the nineties, when Western economies were pivoting toward a postindustrial knowledge economy, creativity was recognized as a precious resource for the economy, and new terms were coined such as the creative industries, creative cities, creative economy and later the creative class and creative society.

She also reminded that creativity is a disruptor, and it is the reason why it is not always welcome in organizations and in society as it cannot be controlled. Creativity has a dual power to open new ideas, forms, practices, or solutions, but also to create confusion, complexity or disorder. In liberal western societies, where personal empowerment, innovation and change are valued, creativity is appreciated, but in more closed, authoritarian, or traditional societies it can be restrained.

Coming back on Art, Bidault-Waddington adds: “it’s really a mistake to see art only as creativity”. There are many other facets to art and some artists are in fact not very creative. Among many other dimensions, some artists aim at working on their singularity and identity, at experimenting, at impacting society, at contributing to history, and so on. Although very important, creativity is only one of the means of art.

When she created her labs in 2000, she wanted to test the borders of art with other domains. In that purpose she created new vocabulary and notions, such as idea engineering and aesthetic or artistic intelligence, to bring her artist’s mind and broader capacities to other fields, and avoid using the too narrow notion of creativity. Designing new concepts happened to be a solution to bridge disciplines. From her perspective, each domain has its specific language, rationale and heritage, which are valuable, important to understand, and should be considered when building these bridges.

Dissolving Disciplinary Boundaries in the Research Process at ICAT

Benjamin Knapp’s Institute for Creativity, Arts and Technology provides a conduit that transcends disciplinary channels in the university for faculty and students to connect across disciplinary silos. It provides spaces for researchers to connect across disciplines and set the stage for creative processes to occur. ICAT funds collaborations such as cinematographer working with a biologist exploring endangered mollusks in the southeastern United States. Using the tool of underwater photography, a cinematographer and biologist worked together to understand and monitor the mollusk environment and activity. The Center hosts “playdates” where the teams connect around the process of art and science collaboration. They have found in these transdisciplinary, collaborative processes that although disciplinary training is essential, the identities fall away during the course of the collaboration. ICAT provides an essential space for the productive “nonlinearity” and “inefficiency” and reciprocal “tension” of creativity to happen.

Boundary work along the spectrum of disciplinarity

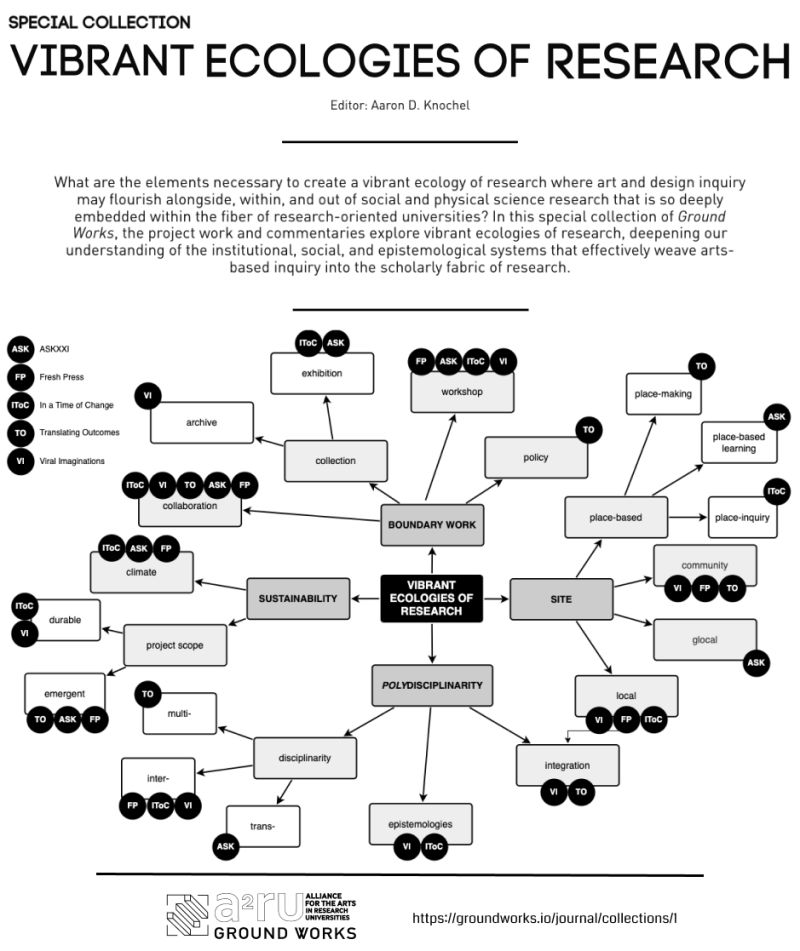

Aaron Knochel says he appreciates the “disciplinary amnesia” that Knapp testified to happening with the ICAT teams. He appreciates what is possible if we could leave behind the legacies of our disciplines or check them at the door a bit more often instead of “carrying them around with us always in the spaces and hallway of schooling and learning institutions.” Coming to this work as an artist and educator, Knochel has to seriously consider the effect of these spaces and how students use them and feel ownership. He has been trying to find inter-, trans- multi-disciplinary kinds a spaces to think about creative and design practice, the ways students interact, and researchers share and benefit from one another. One of the most prominent examples is the movement around maker spaces. He has zeroed in on looking at digital fabrication technologies and found a bridge in technology that enables him to relate to engineers: “While we have very different outcomes and contexts, we share an interest in [the] tools [and] that spirals out into research methodologies [and] conceptualizing curricular frameworks. So oftentimes [technology] is the tool that bridges those disciplines.” Knochel guest edited “Vibrant Ecologies of Research,” a special edition of a2ru Ground Works which explores the ways in which disciplines can come together and sustain the work (or why they are not sustained).

“…while we can talk about arts integration we also need to acknowledge really clearly that artists creative practice and artistic research doesn’t have the same avenues for funding. So we can push back against instrumentalizing the arts in larger science-centric kind forms of research.” –Knochel

The metaphor of Vibrant Ecologies also showcases the type of systemic solutions needed to contribute to planetary health: “How do we come together thinking ecologically in terms of the metaphor of different kinds of resources coming together in different contexts [to solve] the environmental and climate change challenges that we live in.” Knochel is compelled by transdisciplinary research because “we need everybody at the table learning to work with one another to initiate investigation and knowledge formation…that’s my dream as a researcher.” This concept map is a visualization of how the collection of “Vibrant Ecologies of Research” comes together.

Some research questions that emerged in the coming together of the varied projects in the collection include: what is the boundary work of vibrant ecologies? What are these boundaries in institutional spaces? How are [research] sites and research trajectories conceptualized within these interactions? How do we conceptualize the boundary work between communities and higher education institutions? Exploring the boundary work of these ecologies is very important. The “polydisciplinary” mention in the concept map is there as researchers in boundary work often draw on deep disciplinary experience and “codeswitch” to work in different modalities that apply to different instances and contexts. Even within deep transdisciplinary research foundations; disciplinary identification is essential to draw on disciplinary funding sources.

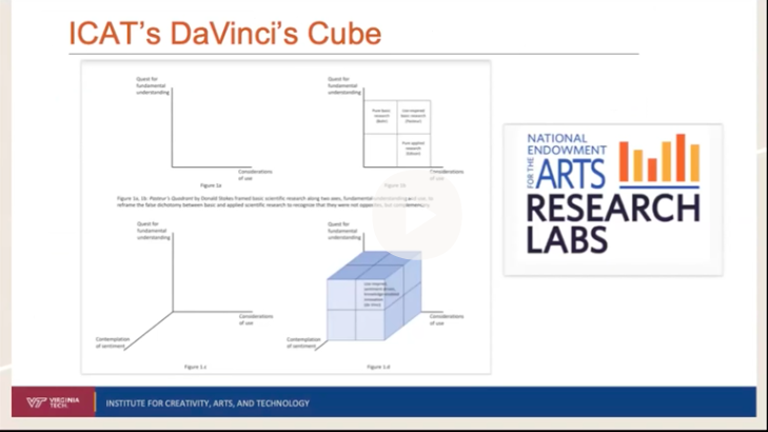

DaVinci Cube Concept

The ICAT team is also looking at creativity beyond higher education by revisiting Pasteur’s Quadrant: a model that presents inquiry as applied and pure research. Stokes presented this model not a spectrum but situated between two axis, with someone like Einstein sitting at quest for knowledge and Edison squarely located in the area of “considerations of use.” At ICAT, they wanted to add a third axis to form a cube (see lower left in figure below), and that is the contemplation of sentiment.

*For a complete visualization of the DaVinci cube, visit: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0N0K2TVzg3g

This expansion of the model accommodates, as an example, one who might be interested in a form or inquiry or doing a project that is purely sentiment. It may be a work of art. It is not necessarily driving new knowledge. It’s affect is on the emotions, causing feeling or sentiment. Looking at industry they are moving across these quadrants, appealing to emotion is important, but they also need to invent new things. People will move to different areas of this cube throughout their careers or even within a single day. What ICAT leaders like about this diagram is that it removes the binary nature between applied and pure characteristics of research—it removes the “antagonism between what is art; and what is creativity.” It allows for these to productively co-exist. It allows for an engineer, for example, to situate the work along this spectrum of creativity, to multidisciplinarity, to a mono-disciplinary approach. It allows for movement.

“What I like about [the cube] is it removes the antagonism between what is art; what is creativity…and it allows for this free movement.”–Knapp

One example of this fluidity would be a marketable invention that started out as an art project—in the area of sentiment; or as it is sometimes called “art for art’s sake.” As part of their work on a new funded project by the (U.S. federal art funder) the National Endowment for the Arts, they are working on finding examples of projects that have followed this path. They know the creative process will be fundamental to many of those stories. Individuals integrate different identities to innovate and may present as an artist, and engineer, or a scientist. They may all avail themselves of creativity. One important thing to track is how scientists and engineers can more freely among the quadrants and not be “stuck” in the “consideration of use” –or applied—area of Stokes’ Pasteur’s Quadrant.

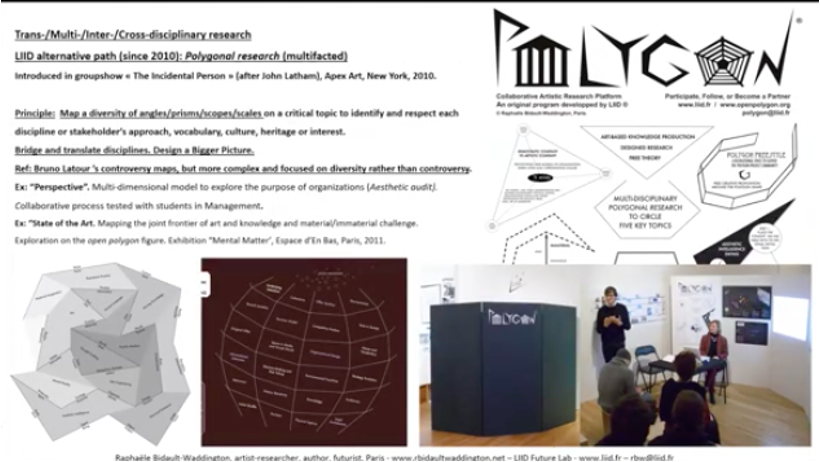

Polygonal Research: a conceptual solution to multidisciplinary research

Stepping beyond the traditional artist’s studio (and role) Bidault-Waddington reconceptualized her work first in relation to three disciplines: arts, economics, and urban design (in practice via collaborations and in theory), and then opened to others, such as digital humanities, science, design and future studies.

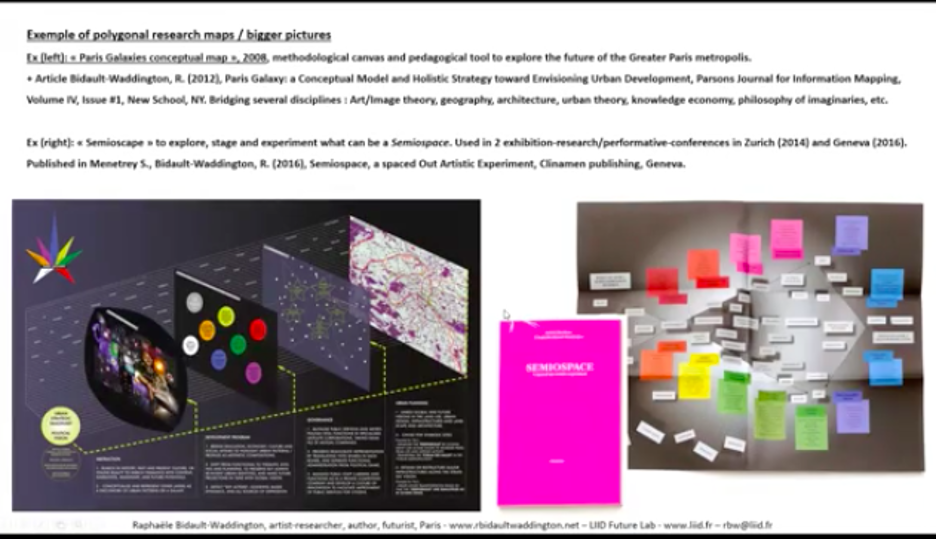

In 2010 she created for “The Incidental Person (after John Latham)” a groupshow at Apex Art, in New York, the Polygon Project to prototype and experiment polygonal research, i.e. a multi-faceted approach to address critical topics from a diversity of perspectives and disciplines. Eventually using design methodologies and conceptual diagrams, it consists in exploring, mapping, and appreciating the insights from different entries (whether disciplines, stakeholders, or persons), to build a multifaced picture of/on a topic. This polygonal approach has been essential to her research on organizations or cities, in a diversity of context such as commissioned project in academic, urban, and economic spheres, or in her independent research. It has also proven to be very useful in futures research, for which it is so important to consider and weave together inputs from different scales and perspectives. It facilitates meaningful conversation between different stakeholders. Conceptual diagrams also help grasping these multiple perspectives, and are empowering tools for teaching complex topics, fostering engagement and lively discussions (in class or in group work). They help establish a common ground as the graphics provide a basic and still fluid order, and set the (open) stage for productive iteration. Polygonal methods allow participants to find their place, contribute to collaborative research and understand those with different language and perspective, not in opposition but as part of a semi-organized and evolutive common bigger picture, the open polygon.

Building Decades of Research: Artist Residency Programs and Interventions

The idea of a serious study in “creativity infrastructure” began in 2013 with IDEAS xLab, co-founded by Theo Edmonds and his husband Josh Miller. One of the founding research questions of the lab was: how can placing artists and their creative processes influence innovation teams in the private sector? (There was also a social impact component with the non-profit sector but Theo did not address this in his talk.)

“It was really focused on not just bringing them together to socialize, but really turning this into an innovation engine that did not question what is the difference between an artist and an entrepreneur, but questioned: What can we do together? If we just start with the fact that the arts have value, entrepreneurship has value, let’s go.”–Edmonds

“Our goal was to understand and deploy artists and our diverse creative practices into catalytic actions that advanced the innovation projects of the companies with who we were working like GE and Humana” Theo said. They started a program called XLERATE ART with an exhibition program in a neighborhood Chamber of Commerce. As the program grew, it served as a unique nexus and gathering place for the cities artists, scientists and business professionals. Together, everyone started exploring how this unique network could become a new type of innovation engine for the city that did not differentiate between the artist and the engineer. One that flattened hierarchies between arts, science and business. In 2014, “Mix and Pivot” was next—meetings that brought together two artists and two entrepreneurs exchanging five-minute pitches about their different ways of looking at aspects of the local economy, then followed by robust discussions and debates. They learned a lot about the nature of these relationships and some of the collaborations are still going in 2023, almost a decade later.

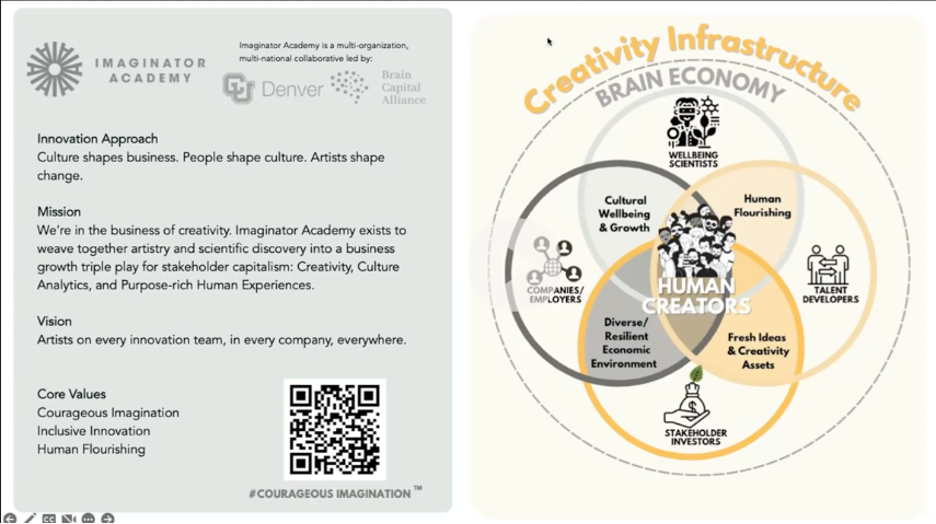

Today, these fundamental questions have grown into a project called Creativity Infrastructure (CIP). CIP advances a multi-national research idea arising from the 3-day Imaginator Summit at CU Denver (October 2022). CIP’s development approach devises and tests a measurable, replicable, scalable creativity infrastructure framework capable of supporting long-term future-of-work research and growth among interdisciplinary teams from arts, science, and business.

Together, the group will advance private sector partnerships to build brain capital (brain health + brain skills) in companies with a specific focus on the brain skill of creativity and the social processes that transform it from latent capacity into innovation (new economic and social value) across diverse industries. Up to twenty companies across two cities, Denver, and Barcelona (Brain Capital Alliance headquarters), will be recruited to participate in the research.

Grounded in state-of-the-science brain capital research from neuroscience, economics, social sciences, and humanities, CIP employs a mixed-methods approach towards two primary objectives.

The first is to validate quantitative brain capital skill assessment tool for use in companies to maximize ROI for innovation investments.

The second is to design a long term research initiative centered on Artist Innovation Residencies (AIRs) as brain capital interventions inside private sector corporations. Primarily researchers will investigate the mediating impact of the artists on team-level novel ideation and cognitive capacity (e.g., creativity, cognitive flexibility, semantic memory); and the antecedent cultural conditions of work environment (e.g., team social well-being) suggested across diverse research disciplines as mechanisms for converting brain capital skills into new organizational-level value. Both economic value produced through the commercialization of products/services and social value produced through areas like corporate social responsibility will be considered.

“How can we keep a sense of the whole, while it’s clear that we cannot grasp the whole…it’s this paradox over understanding or accepting that there [are] many things that we don’t understand and working with uncertainty. And that’s [a] typical question that a part of future research has to address.”–Bidault-Waddington

After the residencies are complete, results will be shared in two museum exhibits (Denver and Barcelona) and use the exhibits for further qualitative research with industry focus groups.

Further Discussion

The balance of the session was a rich dialogue between the roundtable and the audience touching on topics sparked by the case studies, such as the history and current state of research on awe; sound as a tool to foster interdisciplinary pedagogical methods; emotional contagion; the inequitable funding models for different disciplines; the notion of flourishing and its tie to belonging and efficacy. Watch the video embedded above for the full presentations and discussion and make sure you visit the projects mentioned in the roundtable for a fuller picture of artistic research for future challenges.