University of Michigan Public Art Project Illuminates the Concussion Recovery Experience

Jun 23, 2025

Steven Broglio, the Director of the University of Michigan Concussion Center, had been looking for a way to combine art and science to convey the complex experience of concussion recovery for over a decade. He says, “We have really cool fancy equipment here. I can measure amazing things about human physiology and response to concussion and recovery. But I can’t capture the human experience of it, and that’s where the artists are necessary.” When he learned about the U-M Arts Initiative Project Support grants from Arts Initiative Executive Director Mark Clague, he knew the moment had come to realize this long-held ambition.

Broglio and Tina Chen, Managing Director of the Concussion Center, were paired with Jennifer Carty, Curator of Art in Public Spaces at U-M, to develop a proposal for an artist to create a mural depicting the recovery process of Concussion Center patients, to be installed on the Center’s external-facing windows, which overlook one of the School of Kinesiology’s major gathering and event spaces. Carty presented four artists, with a range of styles from highly representative to highly abstract, to be considered for the project. As Carty said, “Envisioning the recovery process could go a million different ways. You can really tackle this project from so many different vantage points, and the results will be wildly different.” One quickly rose to the top: Avery Williamson, a local, Ypsilanti, Michigan based artist, was the unanimous choice to tackle the project.

Carty shared what drew her to Williamson’s work for this project: “What’s so compelling to me is how she’s exploring the emotive quality of mark making, that it’s something that might seem so simple and a tiny gesture, but it really carries so much weight. I was surprised with this project, that these tiny marks really manifest a recovery process in a new way. Also, Avery is such a generous artist with her practice, bringing other people into that process with her.”

With Williamson officially attached to the project, the Concussion Center team’s proposal was approved for funding by the Arts Initiative; the School of Kinesiology and the Concussion Center also provided support for the creation of the work, as well as providing stipends for four student assistants from the Penny Stamps School of Art & Design at U-M.

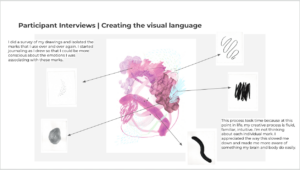

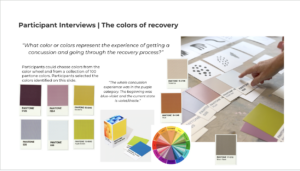

Williamson conceived of an artistic process that would “co-create” the mural with Concussion Center patients. This was accomplished through a series of interviews that invited the patients to describe their injury and recovery experience not only through language, but through image and color, using options shared by Williamson and drawn from her own work. To create the visual vocabulary for the mural, Williamson explained to Michigan News, “I did a survey of my drawings and isolated the marks that I use over and over again…I started journaling as I drew so that I could be more conscious about the emotions I was associating with these marks. In my abstract pieces, I think about holding emotional complexity or competing ideas, or feelings or reactions, that I don’t really have a good verbal way to express, so they come out in the art making as a type of language and release.” This “library” of marks, as well as a Pantone color deck, were core tools for her interviews with seven Concussion Center patients (and one caregiver of a pediatric patient). To find the interview subjects, Chen asked Concussion Center clinicians to recommend patients who might be open to sharing their experience through the interview process and in an artistic medium. Williamson collaborated with the Stamps students to develop the interview guide; several of the students participated in the patient interviews alongside Williamson.

Williamson asked patients to identify marks and colors that resonated with the emotional and physical dimensions of their concussion experience. The graphics below illustrate how Williamson utilized the marks and color deck in her interviews:

Williamson adds: “I really wanted to make a process that was sensitive to the processing challenges post-concussion and felt open and broad, since I was asking them about maybe one of the worst things that’s happened to them. So I wanted people to feel comfortable and heard and like this was a good experience of engaging with art.”

She continued, “I felt such gratitude that they trusted me with their stories. I felt like I was speaking to people about something that had been really transformative in their lives, that made them reflect on their mental health, or how they had felt they could or could not express their emotions or pain previously, or they never had language to express grief. Or they’d say they had a previous concussion that everyone minimized, and then going to the Concussion Center and getting this treatment helped them better understand past injuries. It was gratifying that, if you create the right kind of conditions and spaces to talk with people about things that matter, they’ll go to good and beautiful places. Art really does have the capacity to open up conversation.”

Once Williamson finished the interviews, she drew from the marks and colors selected by the patients to paint a cohesive, multi-panel mural, to be printed onto vinyl and applied to the windows of the Concussion Center offices. Williamson made sure that at least one element from each interviewee was included in the final product. Williamson went through several drafts of the mural before it was presented to the School of Kinesiology’s Space Advisory Committee for final approval; after Williamson tweaked some color selections to better harmonize with the existing color palette of the building, the mural received final approval and was installed in late fall 2024.

Williamson summarized her process in the video below:

Broglio and Chen were thrilled with the final result; Broglio says of the mural, “This is nothing like what I thought it would be but it is everything that it should be.” The response has been overwhelmingly positive from patients and their families, Concussion Center staff, and visitors to the building. Chen added that the School of Kinesiology’s Chief Development Officer always hightlights the mural in tours of the building; “it’s such a great storytelling piece” that has become part of the School’s visual identity. Broglio adds that the mural has also spurred conversation by other units within the School about additional ways to incorporate public art into the Kinesiology building.

The mural also inspired another kind of artistic response to the concussion experience. When Katie Gunning, an administrator for the Dance Department at U-M, read about the project in Michigan News, she thought the mural might provide an excellent starting point–and backdrop–for dance students to share their own, often overlooked, concussion experiences. She shared the idea with Kristen Schuyten, a physical therapist for the department who supports dancers through their concussion recoveries, and Schuyten recruited five dancers to choreograph solos for themselves capturing their experiences, which they performed for the public in front of Williamson’s mural.

Anastasia Bredikhina, one of the dancer/choreographers, shared that each dancer created their piece in isolation, but that seeing all five works together highlighted some of the commonalities of their experiences: “It was a bonding moment, being like, ‘oh I had that symptom too!’ It’s not talked about that much, concussions in dance, so this experience made us feel not as alone.”

Bredikhina suffered her concussion in a dance class after misjudging the distance to the floor during an improvisation exercise. She noted how the invisible nature of the injury complicated her recovery and left her unsure how to behave, or what to share with her teachers or fellow dancers: “I feel like I should be dancing, and should be doing my regular day to day things, because no one else can see it. And I didn’t want people to judge me or to think that I was lying. I didn’t want my professors to think I was half doing things, or just being lazy, but I would get so much more dizzy, more easily. Also my ability to retain choreography and retain movement became less, and I’m a fast learner usually.” She also noted that she experienced symptoms long past the point she expected to, particularly in the dramatic lighting and sound environment of a dance performance technical rehearsal.

She added: “I wanted it to go away so quickly, and it was very weird to navigate. It was very uncertain.” This contrast between her desire for a quick recovery and the slower, non-linear progress of her actual recovery process formed the basis for her solo: “I choreographed moments where I would be really fast, and then some places where I would be really slow to demonstrate my efforts to try to get back to things exactly the way they were, and try to speed back into how fast I was moving before the concussion, and just like a normal day to day activity, and then being halted by such debilitating headaches and stuff which forced me to kind of regress way more than I would have liked to. So that’s how I tried to translate it within the movement.”

Bredikhina feels that the Concussion Center performance has opened up dialogue within the department about the particular challenges that dancers face when they are injured with concussions. She thinks the performance allowed dance students to feel less alone in their experiences, and to identify avenues for support and advice. She also notes that Schuyten has developed a new concussion protocol for the dance department that provides much clearer guidance for students on faculty on what to do when concussions happen.

View the full performance below: